|

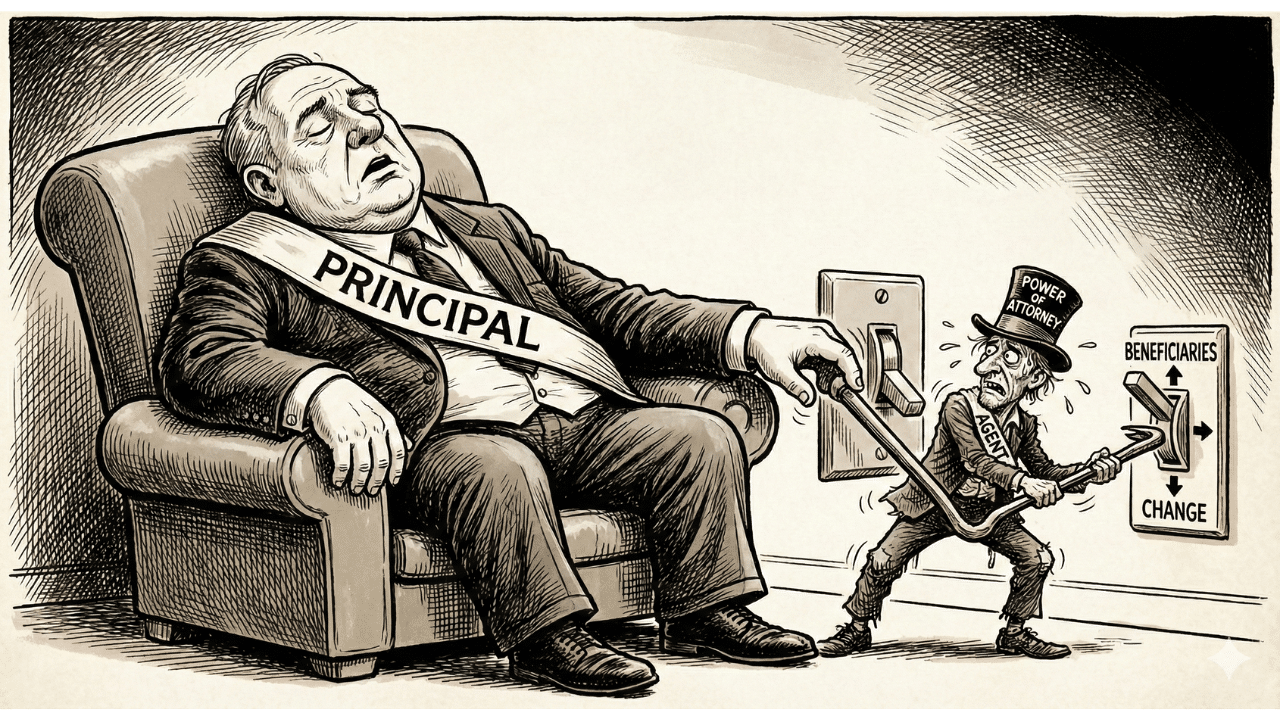

When an Agent (Tries to) Change Estate Beneficiaries

Introduction

In the landscape of Texas estate planning and probate law, few instruments possess the simultaneous utility and danger of the Durable Power of Attorney. It is a document born of necessity—a mechanism to ensure continuity of financial management during a principal’s incapacity—yet it inherently carries the risk of profound abuse. The central question that plagues estate planners, financial institutions, and litigators alike is whether this delegation of authority extends to the ultimate disposition of the principal’s assets. Specifically, can an agent holding a Power of Attorney change the beneficiaries of the principal’s estate, thereby rewriting the legacy of the person they are sworn to serve?

The answer to this question is not a simple binary. It is a complex calculus derived from the interplay of the Texas Estates Code, the Texas Penal Code, and a rich history of common law fiduciary principles. Following the sweeping legislative reforms of 2017, specifically the enactment of House Bill 1974, the legal landscape shifted dramatically. The era of implicit authority has ended, replaced by a regime of “Specific Authority” or “Hot Powers” that demands explicit, granular authorization from the principal.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the legal framework governing beneficiary changes by agents in Texas. It dissects the statutory distinction between general and specific authority, the rigid fiduciary duties that overlay every act of an agent, the procedural mandates for financial institutions, and the severe civil and criminal consequences of overstepping these bounds. By synthesizing the legislative history, appellate case law, and practical operational realities, this document serves as a definitive resource for understanding the limits of agency in the context of estate disposition.

Part I: The Statutory Authority

1.1 The Evolution of the Texas Durable Power of Attorney Act

To understand the current state of the law, one must appreciate the legislative intent behind the 2017 overhaul of the Texas Durable Power of Attorney Act (Subtitle P, Title 2 of the Texas Estates Code). Prior to September 1, 2017, the scope of an agent’s authority was often a matter of interpretation. Agents frequently relied on broad, catch-all provisions—such as the power to perform “any act the principal could perform”—to justify significant estate planning moves, including changing beneficiaries on life insurance policies or retirement accounts.

This ambiguity created a “blank check” problem. Principals, often elderly or in declining health, would sign standard forms intended to help pay bills and manage real estate, unaware that they were potentially handing over the power to disinherit their children or rewrite their wills. Financial institutions, fearing liability from both sides (wrongful refusal vs. facilitating fraud), often defaulted to rejecting POAs, paralyzing the principal’s affairs.

The 2017 amendments, codified largely in Chapter 751 and Chapter 752 of the Texas Estates Code, were designed to resolve these tensions by bifurcating authority into two distinct categories: General Authority (management powers) and Specific Authority (disposition powers).

1.2 The “Hot Powers” Paradigm: Section 751.031

The cornerstone of the modern Texas POA regime is Section 751.031(b). This statute creates a strict prohibition against certain acts unless the power of attorney expressly grants the authority to perform them. These are colloquially known among Texas probate attorneys as “Hot Powers.” The legislature identified these specific acts as having such a profound potential to alter the principal’s estate plan or deplete their assets that they could not be inferred from general language.

Under Section 751.031(b), an agent may take the following actions only if the durable power of attorney designating the agent expressly grants the authority:

- Create, amend, revoke, or terminate an inter vivos trust.

- Make a gift.

- Create or change rights of survivorship.

- Create or change a beneficiary designation.

- Delegate authority granted under the power of attorney.

The significance of this statutory structure cannot be overstated. A principal acts with the intent to delegate management, not necessarily disposition. By isolating these “Hot Powers,” the law forces a conscious decision by the principal. If a Statutory Durable Power of Attorney form is used, these powers are typically presented in a separate section titled “Grant of Specific Authority (Optional),” requiring the principal to initial each specific line to activate the power. If the line is left blank, the power is withheld, regardless of any other broad language in the document.

1.3 Deconstructing the “Beneficiary Designation” Power

Section 751.033 provides the statutory definition for the specific authority to “create or change a beneficiary designation.” It clarifies that this authority empowers the agent to:

- Create or change a beneficiary designation under an account, contract, or other arrangement that authorizes the principal to designate a beneficiary.

- This includes insurance contracts, annuity contracts, qualified or nonqualified retirement plans, and other financial instruments.

This definition is critical because it bridges the gap between the “Specific Authority” section and the “General Authority” sections found elsewhere in the code. For example, Section 752.108 grants an agent general authority with respect to “Insurance and Annuity Transactions,” including the power to “designate the beneficiary of the contract”. However, because Section 751.031 is a limitation on all powers, the general grant in Section 752.108 is effectively neutered regarding beneficiary changes unless the specific Hot Power in Section 751.031 is also initialed.

This interplay resolves the previous confusion where agents argued that the power to “maintain insurance” implied the power to change who received the death benefit. The modern Estates Code makes it clear: maintenance is a management function; changing the destination of the funds upon death is a dispositive act requiring explicit “Hot Power” authorization.

1.4 The “Rights of Survivorship” Distinction

A frequent point of confusion—and litigation—arises from the distinction between “Beneficiary Designations” and “Rights of Survivorship.” While functionally similar in that both pass assets outside of probate upon death, they are legally distinct concepts governed by different subsections of the “Hot Powers” statute.

- Beneficiary Designations (covered by § 751.031(b)(4)) typically apply to life insurance, IRAs, 401(k)s, and Payable-on-Death (POD) bank accounts.

- Rights of Survivorship (covered by § 751.031(b)(3)) typically apply to Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship (JTWROS) accounts or real estate deeds.

An agent who holds the Hot Power to “change beneficiary designations” but not the Hot Power to “create or change rights of survivorship” may find themselves unable to alter a joint bank account, even if they can alter a life insurance policy. This granularity requires precise drafting and a deep understanding of the principal’s asset portfolio. If a principal intends for their agent to have total control over estate planning, both specific authorities must be granted. Conversely, a principal may wish to allow an agent to manage retirement beneficiaries (for tax reasons) but forbid them from altering the survivorship rights on the family home. The statute allows for this precise calibration of authority.

1.5 The “Self-Dealing” Statutory Safety Net

Perhaps the most important protection in the entire Texas Estates Code regarding POAs is found in Section 751.031(c). This provision acts as a statutory failsafe against the most common form of abuse: the agent enriching themselves.

The statute dictates that, notwithstanding a grant of authority to perform a “Hot Power” act, an agent who is not an ancestor, spouse, or descendant of the principal may not exercise authority to create in the agent, or in an individual to whom the agent owes a legal obligation of support, an interest in the principal’s property, whether by gift, right of survivorship, beneficiary designation, disclaimer, or otherwise.

This rule is absolute. Even if a POA explicitly says, “I authorize my agent to change beneficiary designations,” if that agent is not a blood relative or spouse, they cannot use that power to name themselves or their children. The law presumes such acts are inherently self-interested and therefore void, regardless of the principal’s alleged intent.

Example: A wealthy widow names her nephew (not her child) as her agent under a POA, specifically granting him the Hot Power to change beneficiaries. The nephew changes the beneficiary on her $500,000 life insurance policy from her children (the current beneficiaries) to himself. Upon her death, the life insurance company pays the nephew. The children file suit. Result: The beneficiary change is void under § 751.031(c). The nephew must disgorge the funds to the children. Depending on the facts, the nephew may also face criminal charges for financial exploitation.

1.6 The “Presumption of Unfairness” in Transactions

Beyond the outright prohibition of self-benefiting changes, Texas law imposes a broader “presumption of unfairness” on any transaction between an agent and the principal. Under Section 751.103, if an agent engages in a transaction that benefits the agent or someone to whom the agent owes a duty of support, the transaction is presumed to be unfair to the principal unless the agent proves otherwise.

This burden-shifting rule is significant in litigation. In a typical civil case, the plaintiff bears the burden to prove their case. Here, if a disgruntled heir can show that the agent changed a beneficiary designation and the agent’s relative ended up receiving money, the burden shifts to the agent to prove that the transaction was fair, authorized, and in the principal’s interest. This presumption dooms most self-interested beneficiary changes that slip through the Section 751.031(c) prohibition.

Part II: The Fiduciary Duty Overlay

Even if an agent has the statutory “Hot Power” to change beneficiaries and is not self-dealing, every act of the agent remains subject to the stringent fiduciary duties imposed by Section 751.201. The agent must act:

- In Good Faith: The agent must subjectively believe the action is in the principal’s best interest.

- For the Benefit of the Principal: The agent’s motivation must be the welfare of the principal, not the convenience or preferences of third parties (including family members).

- In Accordance with the Principal’s Reasonable Expectations: The agent must consider what the principal would have wanted, to the extent known or reasonably ascertainable.

- Within the Scope of Authority: The agent cannot exceed the boundaries of the POA document.

These duties apply even when the agent is changing a beneficiary designation in a way that does not financially benefit the agent personally.

Example: A father grants his daughter a POA with the Hot Power to change beneficiaries. The father has two other children (the daughter’s siblings). The daughter changes the beneficiary on the father’s $1 million IRA from “divided equally among my three children” to “my daughter and her two children (father’s grandchildren), divided equally.” The daughter argues this is a “better estate plan” for tax reasons. Is this allowed?

- Analysis: While the daughter is a descendant and not technically prohibited under § 751.031(c) (since she did not name herself exclusively), the change fundamentally alters the father’s apparent intent to treat his children equally. Unless the daughter can show this change aligns with the father’s wishes or is clearly in his financial interest (e.g., tax savings that benefit the father during life), this could be a breach of fiduciary duty.

2.1 The Burden of Proof in Disputes

When a beneficiary change is challenged, the courts apply a sliding scale of scrutiny based on the relationship between the agent and the outcome. Texas case law establishes three tiers:

- Direct Self-Dealing: If the agent names themselves as beneficiary, the change is presumed void under § 751.031(c) and the burden is on the agent to overcome a near-insurmountable statutory bar.

- Indirect Benefit: If the agent names a close relative (e.g., their child, who is not the principal’s descendant), the “presumption of unfairness” applies under § 751.103, and the agent must prove the change was authorized and fair.

- No Benefit to Agent: If the agent changes the beneficiary to someone unrelated to themselves (e.g., changing from Child A to Child B, where neither child is the agent), the burden remains with the challenging party to prove breach of fiduciary duty, but courts will still scrutinize the agent’s rationale closely.

Part III: Institutional Response and the “Safe Harbor” for Banks

3.1 Section 751.201: The Duty to Accept the POA

One of the most contentious aspects of the 2017 reforms was the creation of a statutory duty for financial institutions, insurance companies, and other entities to accept a POA that complies with Texas law. Prior to 2017, institutions frequently rejected POAs for a multitude of reasons, leaving agents unable to manage the principal’s affairs.

Section 751.201 now mandates that a person (including a financial institution) must accept a POA that appears to be valid and is presented by an agent within a reasonable time after presentation. Failure to accept a valid POA without reasonable cause subjects the institution to liability for attorney’s fees and costs incurred by the agent or principal in any action compelling acceptance.

However, this duty is not absolute. Section 751.206 provides several grounds for refusal, including:

- The institution believes the POA is not valid.

- The institution believes the agent is acting outside their authority or contrary to fiduciary duties.

- The institution has actual knowledge of the principal’s death or incapacity termination.

- A request for a certification or opinion of counsel under § 751.204 has not been satisfied.

3.2 Requesting a Certification (Section 751.204)

Perhaps the most powerful tool an institution has to protect itself is the right to request a certification from the agent. Under Section 751.204, before accepting a POA, an institution may require the agent to provide:

- An Agent’s Certification: A sworn statement that:

- The principal is alive (or the POA is durable and survives incapacity).

- The POA has not been revoked.

- The agent’s authority has not been suspended or terminated.

- The principal is not subject to a guardianship that has suspended the agent’s authority.

- An Opinion of Counsel: A written opinion from an attorney licensed in Texas that the POA is valid under Texas law and the proposed transaction is within the scope of the agent’s authority.

If the institution requests these documents, the agent has 10 business days to provide them. Failure to do so allows the institution to refuse the POA without liability.

Practical Impact: This provision creates a “gatekeeper” function. If an agent attempts to change a beneficiary designation and the insurance company requests an Opinion of Counsel, the agent must hire a lawyer who is willing to put their professional reputation on the line by certifying that the change is authorized and proper. Most reputable attorneys will refuse to provide such an opinion if the facts suggest self-dealing or lack of proper Hot Power authority. This procedural hurdle prevents many improper beneficiary changes before they occur.

3.3 The “Red Flag” Doctrine

Even with a valid POA and certification, institutions are not required to blindly facilitate transactions that raise red flags of financial abuse. Texas courts have recognized a common-law duty for financial institutions to investigate suspicious activity, particularly involving elderly principals.

- Example Red Flags:

- The agent suddenly changes a beneficiary designation that has been in place for decades.

- The change benefits the agent or their family.

- The agent is a recent acquaintance of the principal (e.g., a caregiver, not a family member).

- The principal has cognitive impairment or is in a nursing home.

- The agent refuses to allow the institution to speak directly with the principal.

When such red flags exist, institutions may freeze the account and request court intervention, even if the POA is facially valid. While this can be frustrating for legitimate agents, it serves as a critical line of defense against elder financial abuse.

Part IV: Case Law Illustrating the Limits of Authority

4.1 Huie v. DeShazo (2019) – The “Hot Power” Trap

In Huie v. DeShazo, the Texas Court of Appeals addressed a classic scenario where an agent attempted to change a beneficiary designation without proper authority.

Facts: Mary executed a POA naming her daughter, Jane, as her agent. The POA included broad language like “to manage all of my affairs” and “to act as I could act.” However, the POA was drafted before the 2017 amendments and did not include the specific “Hot Power” initials. Mary had a life insurance policy naming her son, Tom, as the sole beneficiary. Jane, using the POA, changed the beneficiary to herself and her children.

Issue: Was Jane’s change of beneficiary valid under Texas law?

Holding: The Court held the change was invalid. Even though the POA predated the 2017 amendments, the court applied the principle that the power to change a beneficiary designation is a “dispositive power” that must be expressly granted, not inferred from general management language. The court noted that pre-2017 law also recognized limits on implied authority for significant estate planning acts.

Outcome: The life insurance company was ordered to pay the death benefit to Tom. Jane was ordered to reimburse any benefits she had received. The court also awarded attorney’s fees to Tom and referred the matter to the district attorney for potential criminal investigation.

4.2 Estate of Martinez v. Garcia (2021) – Undue Influence via POA

Facts: Roberto, an 82-year-old widower with dementia, executed a POA naming his neighbor and caregiver, Maria, as his agent. The POA included the “Hot Power” to change beneficiary designations. Maria changed the beneficiary on Roberto’s $300,000 IRA from his three children to herself. Roberto died six months later. The children sued, alleging undue influence and breach of fiduciary duty.

Issue: Was Maria’s beneficiary change valid, given that she had proper Hot Power authority under the POA?

Holding: The Court held the change was void for two independent reasons:

- Violation of § 751.031(c): Maria was not Roberto’s descendant, spouse, or ancestor. Therefore, she could not use the Hot Power to benefit herself, regardless of the language in the POA.

- Undue Influence: Even if the statutory prohibition did not apply, the court found that Maria exercised undue influence over Roberto. The POA was executed during a period of cognitive decline, and Maria isolated Roberto from his children during the critical months before his death.

Outcome: The IRA funds were ordered paid to the estate for distribution to the children. Maria was also found liable for breach of fiduciary duty and ordered to pay punitive damages. The court imposed a constructive trust over other assets Maria had taken.

Part V: Civil Remedies for Breach

5.1 Claims Available to Injured Beneficiaries

When an agent improperly changes a beneficiary designation, the original beneficiaries have several potential causes of action:

- Breach of Fiduciary Duty: The agent violated their duty of loyalty or duty of care.

- Fraud: The agent made false representations to the insurance company or institution.

- Tortious Interference with Inheritance: The agent intentionally interfered with the beneficiary’s expectancy.

- Unjust Enrichment: The agent was unjustly enriched at the expense of the rightful beneficiaries.

- Conversion: If the agent received funds, they converted property that rightfully belonged to others.

5.2 Remedies

Texas courts have broad equitable powers to remedy breaches of fiduciary duty:

- Voiding the Transaction: The court can declare the beneficiary change void and order the funds paid to the original beneficiaries.

- Damages: Actual damages, plus punitive damages if the agent acted with fraud or malice.

- Constructive Trust: If the funds have already been paid to the agent, the court can impose a constructive trust, treating the agent as a mere holder of the funds for the rightful owners.

- Fee Shifting: Under Section 751.251, the court may award reasonable attorney’s fees to the prevailing party.

- Removal: The court can remove the agent and appoint a successor.

- Disgorgement: The agent may be required to repay any compensation received for their services.

5.3 The Statute of Limitations

The statute of limitations for breach of fiduciary duty in Texas is four years. The clock typically begins to run when the claimant knows or, in the exercise of reasonable diligence, should have known of the breach.

- The Discovery Rule: In the context of beneficiary designations, the breach (the change of the form) often happens years before the harm (the death of the principal). Courts generally apply the “discovery rule,” holding that the limitation period does not start until the beneficiary discovers the change—which is usually upon the principal’s death when the insurance company denies their claim.

Part VI: The Criminal Dimension

Beyond civil liability, agents face significant criminal exposure. Texas has aggressively strengthened its laws against elder abuse.

6.1 Exploitation of the Elderly (Penal Code § 32.55)

Texas Penal Code Section 32.55 creates a specific offense for “Financial Abuse of Elderly Individual.” The statute defines “financial exploitation” to explicitly include “the breach of a fiduciary relationship, including the misuse of a durable power of attorney.”

- Elements: The state must prove the agent knowingly engaged in the wrongful taking, appropriation, or use of the elderly person’s property.

- Grading: The offense is graded based on the value of the property. Misappropriating over $150,000 (a common value for a home or life insurance policy) is a first-degree felony, carrying a potential sentence of 5 to 99 years in prison.

- Relationship of Confidence: The statute applies to anyone in a “relationship of confidence or trust,” which is statutorily defined to include agents under a POA.

Prosecutors are increasingly willing to indict agents who use POAs to drain accounts or redirect beneficiary designations to themselves, viewing these acts not as “civil disputes” but as theft.

Part VII: Practical Guide and Strategic Considerations

For practitioners, principals, and agents, the complexity of this law dictates a cautious and precise approach.

7.1 For Principals: Drafting with Intent

The “Hot Powers” section of the Statutory Form is not a checklist to be completed blindly.

- Default Recommendation: For most clients, the default advice should be not to initial the Hot Powers regarding beneficiary designations or survivorship. The risks of fraud or inadvertent disinheritance usually outweigh the convenience.

- Special Instructions: If the power is necessary (e.g., for Medicaid planning), use the “Special Instructions” section to limit it.

- Sample Restriction: “My agent may change beneficiary designations ONLY to name my descendants, per stirpes. My agent is prohibited from naming themselves or their family as beneficiary.”

7.2 For Agents: The “Safe Harbor” Protocol

If you are an agent considering a beneficiary change:

- Verify Authority: Locate the specific initialed line in the POA. Without § 751.031(b)(4) authorization, stop.

- Verify Eligibility: Are you a descendant, ancestor, or spouse? If not, § 751.031(c) prohibits you from benefiting.

- Document the “Why”: Create a paper trail. Why is this change in the principal’s best interest? (e.g., “Principal is entering a nursing home; moving assets to a compliant annuity to preserve Medicaid eligibility”).

- Get an Opinion: Have a lawyer review the POA and the proposed change. Requesting a Section 751.204 Opinion of Counsel provides a layer of defense against future “bad faith” claims.

- Communicate: If possible, inform other family members. Secrecy is a hallmark of undue influence; transparency is the best defense against it.

7.3 Comparison of General vs. Specific Authority

The following table illustrates the crucial difference between the powers agents think they have and the powers they actually have under the 2017 Act.

| Action Desired | General Authority (Likely Insufficient) | Required Specific “Hot Power” |

|---|---|---|

| Buy Life Insurance | § 752.108 (Insurance Transactions) | None (General Authority is sufficient) |

| Change Insurance Beneficiary | § 752.108 (Insurance Transactions) | § 751.031(b)(4) (Change Beneficiary) |

| Open Joint Bank Account | § 752.106 (Banking Transactions) | § 751.031(b)(3) (Survivorship Rights) |

| Fund a Revocable Trust | § 752.109 (Trust Transactions) | § 751.031(b)(1) (Create/Amend Trust) |

| Gift Cash to Grandchild | § 752.103 (Stock/Bond Transactions) | § 751.031(b)(2) (Make a Gift) |

Conclusion

The question “Can a Power of Attorney change estate beneficiaries?” can be answered with a qualified “Yes,” but the path to that “Yes” is fraught with statutory pitfalls and fiduciary landmines. The Texas Legislature, through the 2017 amendments, made a policy decision to favor protection over convenience. By requiring explicit “Hot Power” authorization, the law acknowledges that the power to designate beneficiaries is tantamount to the power to write a will.

For the agent, this power is a heavy burden. It requires strict adherence to the duty of loyalty and the “presumption of unfairness” rule. Any deviation that benefits the agent will be viewed with extreme skepticism by the courts. For the principal, the power of attorney remains the most dangerous document in their estate plan—a necessary tool that, without precise drafting and careful selection of the agent, can dismantle their legacy.

As the body of case law surrounding the 2017 Act matures, we can expect courts to continue enforcing the strict boundaries of Specific Authority. In the interim, the prudent course for all parties is one of caution, transparency, and rigid adherence to the four corners of the statutory text.

Contact Us

The attorney responsible for this site for compliance purposes is Ryan G. Reiffert.

Unless otherwise indicated, lawyers listed on this website are not certified by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization.

Copyright © Law Offices of Ryan Reiffert, PLLC. All Rights Reserved.